Since Article 50 was triggered, there are some recurring themes in the EU debates that rage across my social life that warrant some scrutiny. It’s always good to fact-check, and I’m afraid you are mythtaken on some issues. The facts:

The European Union is not very nice to migrants if they’re not European.

“Migrants who are refused entry to the EU and dispute the decision should be detained to prevent them staying illegally, the European Commission said Thursday as it unveiled measures to get tougher on migration.

People who have been told they will be returned to their home country and “show signs they will not comply, such as refusal to cooperate in the identification process or opposing a return operation violently or fraudulently” should be detained to “prevent absconding,” the Commission said in a statement Thursday.

Migration commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos said the measure was “in full compliance” with human rights laws and it would “not only take pressure off the asylum systems in member states and ensure appropriate capacity to protect those who are genuinely in need of protection, it will also be a strong signal against taking dangerous irregular journeys to the EU.”

It’s not a call for blanket detention, said a Commission official, but a way to make full use of European legislation which allows irregular migrants to be detained for six months, and in some cases for 18 months. The official added that the move is to stop migrants disappearing while their claim is being processed.

In 2015, the number of irregular migrants ordered to leave the EU was 533,395, up from 470,080 in 2014, according to Commission figures. That figure could top 1 million once all outstanding asylum applications have been processed.”

See also the Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants Facebook Page for a constant stream of stories Remain voters don’t want to hear.

The European Union has, in fact, started reforming itself in the wake of Brexit.

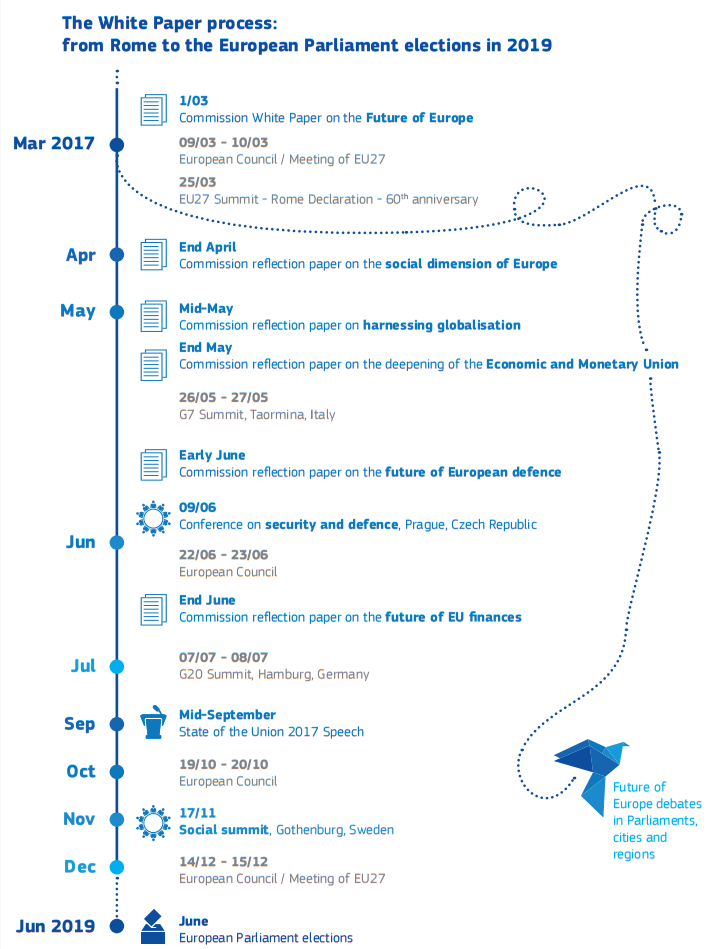

Below: the White Paper on the Future of Europe, which is kicking off a two year process of consultation and debate on EU reform in every EU nation. Although the content is dominated by complaints by the European Commission about how mean the 27 are to them and how they need to stop being mean and also set up an EU Army, it’s good to see that the conversation about EU reform is finally a reality instead of empty pipe dreams and promises. Shame Britain had to leave to make it happen.

“Too often, the discussion on Europe’s future has been boiled down to a binary choice between more or less Europe. That approach is misleading and simplistic. The possibilities covered here range from the status quo, to a change of scope and priorities, to a partial of collective leap forward. There are many overlaps between each scenario and they are therefore neither mutually exclusive, nor exhaustive.”

Scotland isn’t going to be joining the European Union without giving up the pound and its economic independence.

Sorry.

“An independent Scotland would have to go through the accession process, so it would not be automatic,” said Fabian Zuleeg, the chief executive of the European Policy Centre thinktank. “As Scotland does largely fulfil the [membership] criteria it would be a relatively smooth process.”

He said it was difficult to predict how long accession talks would take, but he would expect “some kind of interim arrangement” while Scotland detached itself from the UK.

Kirsty Hughes, an expert on EU policy based in Edinburgh and a former European commission official, said she and other colleagues believed it would take until about 2022 or 2023 for an independent Scotland to join the EU, even if a referendum was staged before Brexit. Scotland would also have to commit to joining the euro at a later stage.

Scotland was likely to be fast-tracked since it would be in accord with EU regulations. But Hughes added: “It’s very hard to see it being less than three to four years [after a referendum in 2019], even going through the process pretty quickly.”

Independent Scotland ‘would have to apply to join EU’ – Brussels official

“All EU Member States , except Denmark and the United Kingdom, are required to adopt the euro and join the euro area. To do this they must meet certain conditions known as ‘convergence criteria’.

An accession country that plans to join the Union must align many aspects of its society – social, economic and political – with those of EU Member States. Much of this alignment is aimed at ensuring that an accession country can operate successfully within the Union’s single market for goods, services, capital and labour – accession is a process of integration.

Adopting the euro and joining the euro area takes integration a step further – it is a process of much closer economic integration with the other euro-area Member States. Adopting the euro also demands extensive preparations; in particular it requires economic and legal convergence.”

Enlargement of the Euro area – Who can join and when?

Scotland is probably not going to declare independence in order to rejoin the European Union – because Scots don’t want to join.

“Just a day after the Scottish First Minister demanded a second vote on independence, senior Nationalist sources told The Daily Telegraph that Ms Sturgeon would instead try to join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), whose members include Norway and Iceland.

Nationalist sources said that Ms Sturgeon saw EFTA membership as a more realistic goal than full EU membership, and suggested an independent Scotland could decide whether it wanted to join the EU at a later date, perhaps after a third referendum.

Ms Sturgeon fears that the SNP’s long-standing policy of an independent Scotland joining the EU would put off the 400,000 voters who backed independence in 2014 and also voted Leave in last year’s EU referendum. They represent one quarter of all those who voted for independence.

…

Alex Neil, a former minister in the Scottish Government, backed the plan and argued that the Nationalists had to “decouple” independence from the EU if they were to give themselves the best chance of winning.

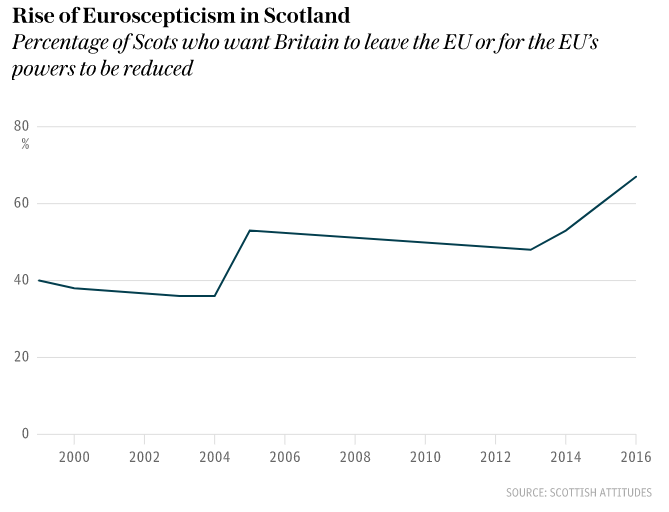

The annual Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, published on Wednesday, highlights a surge in Euroscepticism, prompting the authors to warn that “focusing on EU membership may not be the best way to swing voters in favour of Yes”.

Although the authoritative study found record support for independence at 46 per cent, it also said 25 per cent of voters want Britain to leave the EU, with another 42 per cent wanting EU powers to be reduced, totalling 67 per cent of people holding Eurosceptic views.

The equivalent figure was 53 per cent in 2014 and 40 per cent when devolution started in 1999.”

You mean there are options for a nation’s relationship to the EU besides In or Out? And that maybe Scottish people aren’t a monolithic cheerleader for Europe? And that maybe international politics is complex and nuanced?

Well, I’ll be blown over with a gooseberry.

The British public agree with me on desired negotiation outcomes

On sovereignty and tariff-free Single Market access – the public not only agree with me, so does the Labour Party’s 2017 manifesto.

“The findings, from the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) think tank, are in part a vindication of Theresa May’s Brexit strategy. From the off, she made control of immigration her primary red line. That’s an approach that chimes with the British people. A resounding 68 percent want Brexit to mean that EU migrants are treated the same as non-EU migrants — in other words, an end to freedom of movement.

Interestingly, that includes 54 percent of Remain voters.

However, maintaining free trade with the EU is more popular than ending freedom of movement: 91 percent of Remain voters support continuing free trade, and so do a whopping 88 percent of Leave voters.…

Of course, the crux of May’s Brexit negotiation will be a trade-off between the popular benefits of EU membership and her wish to exempt the U.K. from the bits that the public doesn’t like. NatCen has done some polling here too. Asked whether they would be willing to accept freedom of movement in order to achieve free trade with the EU, there is a majority (54 percent for versus 44 percent against) in favor of such a trade-off.”