Guy Verhofstadt is the leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats grouping in the European Parliament, of which the Liberal Democrats are the UK section. In 2018, he delivered these remarks to the ALDE Congress regarding a European Army.

If you voted Liberal Democrat in the Euros, a single European army with firepower to match the US military and which might go to war with Russia is what you voted to support.

“A new Europe, a really true sovereign Europe, able to protect its borders, able to protect its interests is the next thing that we need to do. To stand up, if necessary, against Putin, if it is necessary. Do you know what the figures are today, dear friends? You know what the figures are? We, the European countries are spending 40-45% of the budget of the American army, but we are only capable to fulfil 10-15% of the operations of the American army.

Even I, I am a lawyer, so I know nothing about mathematics, nevertheless I was a minister of budger – you don’t need to know anything about mathematics, only the word NO. But I have to tell you, I am a lawyer, but even I know we are three to four times less efficient than the Americans. Moreover, the reality is we spend three times more than the Russian Federation on military, but I’m not sure if the Russian army comes towards our borders, we are capable of defending ourselves without American help.

It was President Macron in a speech during the commemoration of the First World War who said 28 different armies, it’s a waste of money and at the same time it is a danger for our collective security and that has to change in Europe. So, that’s our project.”

Guy Verhofstadt is not a hugely powerful figure in the European Parliament, but this is not a marginal idea. At a European Commission Presidential debate in March 2019, Manfred Weber, the leader of the European People’s Party (the European Parliament equivalent of the Tories and the largest party), also supported a unified European Army (and FBI!):

Some of the sharpest clashes between the candidates were on the question of whether the EU should aspire to develop an army — with Verhofstadt and Weber generally in favor, and [Frans] Timmermans [Party of European Socialists – Labour is in this grouping] and [Ska] Keller [European Green Party] expressing skepticism if not outright opposition.

Politico (Mar 2019): “ Frenzy in Firenze: 4 takeaways from EU lead candidate debate “

“European army!” Verhofstadt declared after expressing his agreement with Weber that there should be an EU version of the FBI.

“The biggest waste of money in the European Union is the military, the way we organize it,” Verhostadt said. “We spend nearly half of the Americans. We spend three times more than the Russians on military in Europe, but I am not sure if the Russians come this way that we are capable to stop them. A European army of 20,000 people in 2024. Let’s do it.”

Timmermans disagreed with the FBI proposal, and was especially dismissive of talk of an EU army. “Don’t overpromise,” he said. “There is not going to be a European army anytime soon.”

Weber jumped in on Verhofstadt’s side. “We should have great ambitions,” he said, adding: “It’s a fundamental idea to never have war again in Europe. It’s today unthinkable but with a common European army it would be totally unthinkable.”

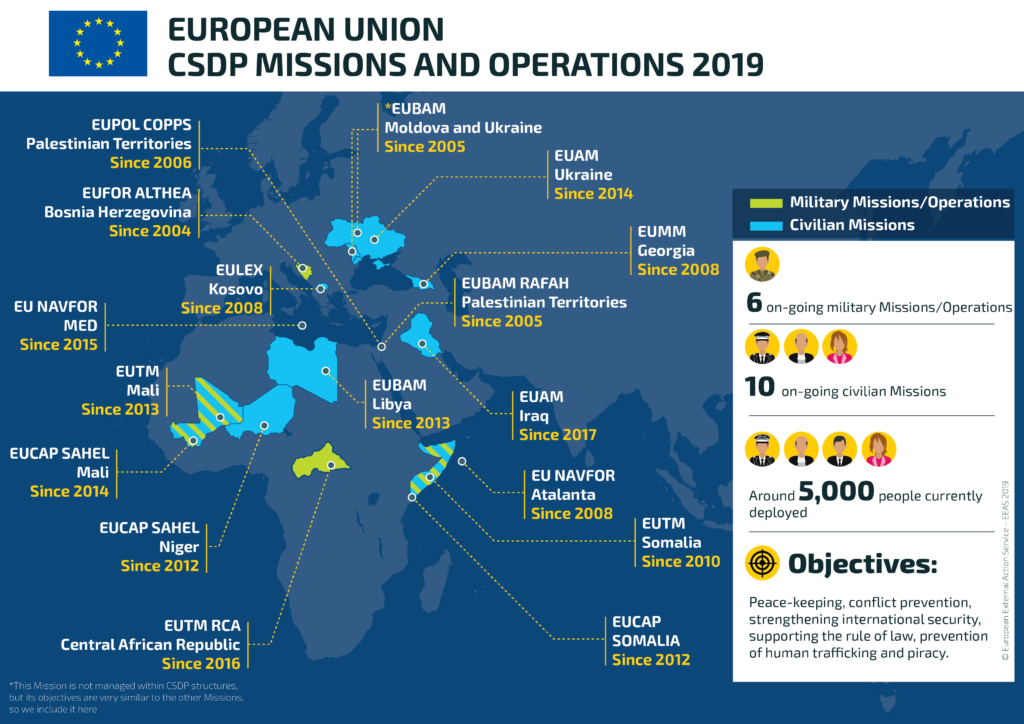

As is its wont, regardless of the political lip service, the EU is quietly getting on with a unified military capacity anyway with the start of an arms race and the ironically named European Peace Facility:

It would be easy to dismiss the idea [of a European Army] as just a political gimmick, if it were not for the fact that European defence has gone through some significant transformation over the last few years.

Largely thanks to Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, European governments have realised that defence budgets can no longer be expendable lines in national budgets. In 2015–16, for the first time in decades, European defence budgets stopped their post-Cold War decline, and most are now on the increase. Even if Europe still falls short of the 2% defence-spending target – the average among European NATO members is 1.44% – it is now closing the US$102 billion gap. (In 2014, the gap was US$138bn.)Added to this recovery in defence spending, European countries have strengthened their armed forces’ readiness and in some cases deployed them under the NATO banner on the eastern flank of Europe, something seldom seen since the end of the Cold War.

The European Union has started mobilising significant resources as well. Launched in early 2017, the European Defence Fund is set to reach €1.5bn in 2021, and the Commission hopes to leverage an additional €4bn in investments from member states, for a total of €5.5bn (around US$6.2bn). Equivalent to the entire Swedish defence budget in 2018, this will bring much-needed cash to some of the weakest areas of the European defence sector: research and development, and new equipment acquisition.

In addition, in June last year EU High Representative Federica Mogherini proposed the establishment of a European Peace Facility, a fund of potentially €10.5bn annually, which, if agreed, could be used as early as 2021 to cover some of the costs of the military operations led by European armed forces and even regional partners. Despite its name, this would be the first time that the EU has freed up funds to support military operations. This has long been France’s wish after years of opposition by Germany, which has argued that the EU treaties forbid providing support to military activities and even capabilities, and a systematic veto from the UK, which perceived it to be in direct competition with NATO.

Of course, there is a difference between new funds and institutional measures on the one hand, and a combat-ready army of European soldiers on the other. But the EU is fast becoming a real actor in defence where it used to be a marginal one: between 2021 and 2027, the EU aims to invest €13bn in defence research and development, and equipment, and €6.5bn for military mobility, to which one may add the off-budget €10.5bn fund for the European Peace Facility.

International Institute for Strategic Studies (Jan 2019): “A European army: can the dream become a reality?”

Thankfully, this project is having some delays due to the inconvenient decision of Britain to vote to leave the European Union and take our top ten most powerful military in the world with us. A November 2018 study by the International Institute of Strategic Studies (a leading defence policy think-tank based in the UK) and the German Council on Foreign Relations, “Protecting Europe: meeting the EU’s military level of ambition in the context of Brexit” (which you can download here) found that the EU would find it frustratingly difficult to invade Africa, Central Asia, and South East Asia simultaneously without us on board. If we leave the European Union, that’s one of the most powerful militaries in the world not going anywhere near that project, which the wonks have acknowledged would hamstring its “peace-keeping” operations the world over for decades due to our naval power:

The EU Global Strategy (EUGS) has led to some adjustments but not to a wholesale review of military-planning assumptions. The relevant scenario families are therefore peace enforcement (up to 4,000 kilometres from Brussels); conflict prevention (up to 6,000 km from Brussels); stabilization and support to capacity-building (up to 8,000 km from Brussels); rescue and evacuation (up to 10,000 km from Brussels); and support to humanitarian assistance (up to 15,000 km from Brussels).

EU member states want to be able to conduct more than one operation at a time in the CSDP frame- work. It is this concurrency of operations that will create real stress on capabilities, much more so than any one of the scenarios mentioned above taken by itself. Moreover, sustainability is a problem. While short-term operations might be possible when using all available assets, those requiring one or more rotations will overstretch European armed forces.

Of the IISS-DGAP scenarios, only the rescue and evacuation operation (located in South Africa) and the support to humanitarian-assistance operation (located in Bangladesh) did not generate any capability shortfalls if the current 28 EU member states (EU 28) contribute to the force pool. If the United Kingdom is omitted (EU 27), the humanitarian-assistance operation faces a shortfall in the naval domain.The scenarios concerning peace enforcement (located in the Caucasus), conflict prevention (located in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean), and stabilization and support to capacity-building (located in Somalia/Horn of Africa) would all create significant capability shortfalls, even when the EU 28 is considered.

World Economic Forum (Dec 2019), “Can the EU deliver on its military ambitions after Brexit?”

The EU 27 would face much greater shortfalls, in particular because the UK would be able to provide important enabling and high-end capability in each case. Under those circumstances, a successful implementation of the operation is doubtful.

The UK is one of the most powerful military nations in the world but because of our focus on technology and diplomatic leverage instead of troops, our navy is incapable of independent military operations. Removing us from EU military cooperation as much as possible hamstrings them because they don’t have easy access to our resources and hamstrings our ability to go to war with anyone else.

Just a thought.